Five Books That Changed the Way We Think About Ottoman History

A couple of months ago, I wrote about five books that offer a good introduction to anyone interested in learning about Ottoman history.

This week, I’d like to go a little deeper and present you with five key works that have played an important role in shaping our understanding of the Ottoman Empire.

As was the case with my earlier post, I’ll include links for those who’d like to check out the books in more detail. I don’t, however, have any affiliations with the publishers.

Cemal Kafadar, Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State, University of California Press, 1996

If you want to understand early Ottoman history, this book is a must-read.

In it, Cemal Kafadar examines the factors behind the Ottomans’ rise from a small principality in northwest Anatolia to a global empire by the 16th century.

He argues that the emergence of the Ottomans was a product of the distinctive culture and ethos of the frontier environment, of which the “gazis” (Islamic holy warriors) were a crucial part. According to Kafadar, the Ottomans were more successful than other Turkish principalities in the region in harnessing this frontier ethos for their own territorial ambitions.

Equally important, Kafadar demonstrates that even as the Ottomans leveraged the frontier dynamics, they also worked to create a centralized state. In this vein, they eventually tamed the frontier spirit by marginalizing the frontier warriors or assimilating them into the official hierarchy from the late 14th century. Combined, these factors contributed to the success of the Ottomans between the 14th and 16th centuries.

Even though the book was published almost 30 years ago, Kafadar’s work continues to be a crucial resource for understanding the origins of the Ottomans. It’s a work I keep going back to again and again, and it’s highly recommended.

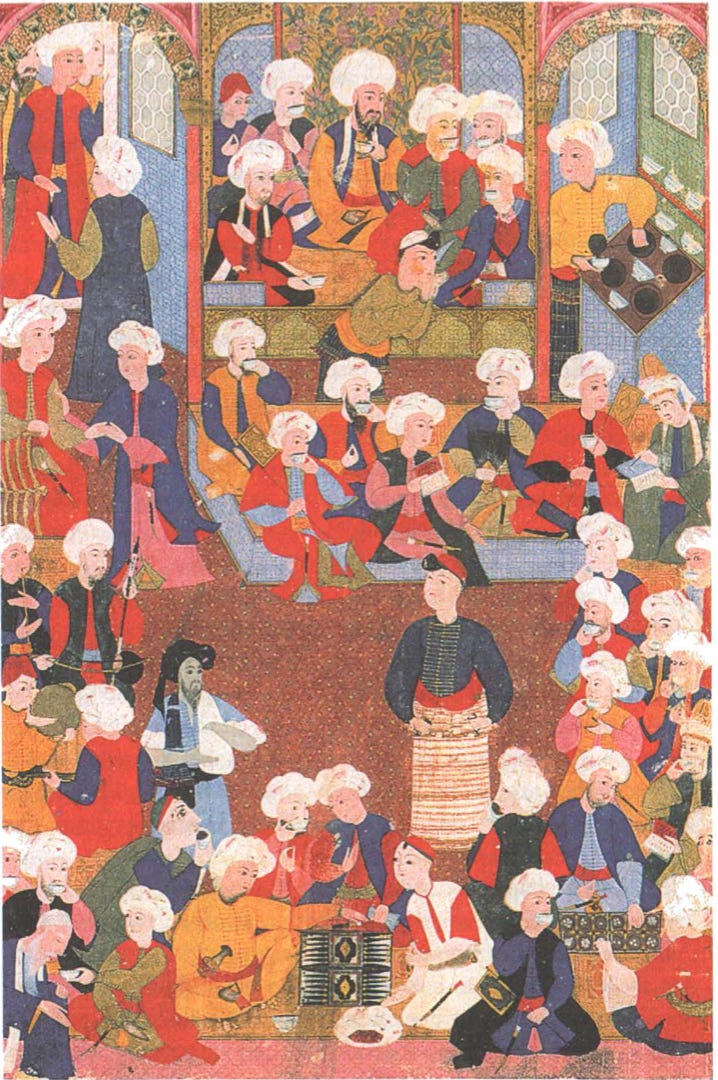

Leslie Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, Oxford University Press, 1993

People, especially in the West, have long been fascinated by the idea of the “harem.” This was particularly true of the Ottoman imperial harem, often regarded as the “harem par excellence.”

They imagined it as a place where the sultans indulged freely in debauchery, fulfilling their sexual fantasies with hapless concubines, who were powerless and secluded from the outside world.

In this seminal work, Leslie Peirce offers a powerful corrective to this narrative. She presents the Ottoman imperial harem as a bureaucratic institution with its own rules and hierarchical organization. She also demonstrates how, from the mid-16th century onwards, women in the harem started to have a considerable influence in Ottoman politics, while they also projected their power outside through works of philanthropy.

Peirce’s book was also a pioneering work of history in the sense that it was one of the first books that brought the concept of gender into Ottoman history writing.

If you want to know more about the role that the imperial harem played in Ottoman history, you can’t do better than Peirce’s book.

You can also check out my review of it, which I wrote a while back.

Şevket Pamuk, A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2000

This is one of the best economic history books written on the Ottoman Empire.

In it, Şevket Pamuk (brother of the famous novelist, Orhan Pamuk) presents a detailed history of the monetary state of the Ottoman Empire. Pamuk takes an empire-wide and chronologically comprehensive approach to the subject, arguing that by focusing on the monetary history, we can reach several key conclusions about the general history of the Ottoman Empire.

Pamuk examines a number of key themes in the book, including the debasement policy implemented by Mehmed II to finance his wars, the effects of the “Price Revolution” on the Ottomans, and how inflation plagued the Ottoman state in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

One important argument that he advances in the book is that, contrary to what the conventional scholarship believed, the Ottomans generally implemented a policy of “selective interventionism” when it came to economic matters. Pamuk also demonstrates that the Ottoman government never aimed to have a unified monetary system, opting instead for a more flexible approach. Finally, the periodization that he proposes in the book also has major implications for Ottoman history writing on the period 1600-1800.

If you like economic history or would like to get an economic perspective on Ottoman history, you can’t do better than this book.

Madeline Zilfi, Women and Slavery in the Late Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2010

Slavery in the Ottoman Empire is usually analyzed as different from other types of slavery around the world, such as in the United States. It is often assumed to have been more “benevolent” and treated as a unique case.

In this work, Madeline Zilfi goes beyond this paradigm and argues that slavery in the Ottoman Empire, even the domestic kind, was characterized by cruelty, sexual abuse, and deprivation. She also demonstrates how female slavery was central to the Ottoman imperial system in the 18th and 19th centuries, especially when it came to elite reproduction.

Zilfi’s work is important in bringing together the concepts of gender and slavery to provide a sustained analysis of the political and social life in the late Ottoman Empire. If you’re interested in these topics, I’d highly recommend Zilfi’s book.

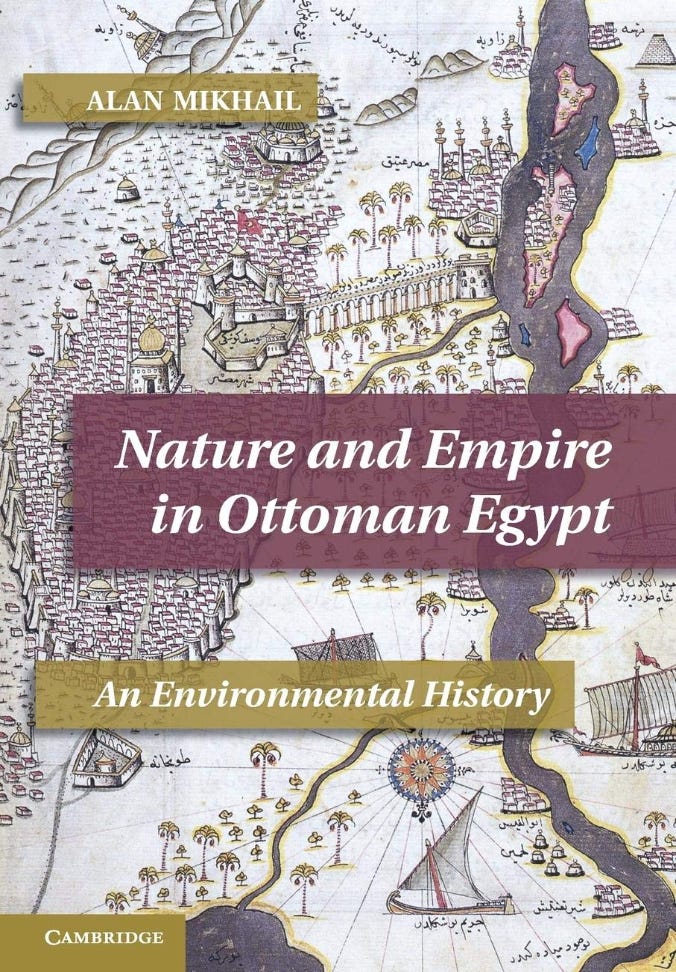

Alan Mikhail, Nature and Empire in Ottoman Egypt: An Environmental History, Cambridge University Press, 2011

This is a groundbreaking work. With this book, Alan Mikhail introduced the “environment” as a tool of analysis in Ottoman historiography, opening up new ways to understand the Empire’s history.

The book is an examination of Ottoman Egypt through the lens of the environment between the years 1675 and 1820. Mikhail argues that in the early modern period, the Ottoman Empire had an imperial network of resource allocation and balance, of which Egypt was a crucial part. In this system of resource allocation, Egypt played the role of food producer and supplied Istanbul and the rest of the Empire with foodstuffs, while wood was brought into Egypt because it was crucial for Egypt’s irrigation network.

Mikhail claims that Egyptian peasants had “near-absolute authority” over the functioning and repair of Egypt’s irrigation network because the peasants benefited from the irrigation system themselves, and because they were the ones who had specialized knowledge about their local irrigation infrastructure and the environment. At the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, however, this system of imperial resource allocation, based on local expertise, was replaced with a more authoritarian and centralized resource management mechanism.

According to Mikhail, as Egypt moved away from being the most important province of the Empire towards a more sovereign entity at the beginning of the 19th century, it started to break away from the system of imperial resource management, which led the exceedingly centralized and authoritarian bureaucracy of Egypt to demand more from its peasants. As a result of this process, Mikhail argues that the centralized bureaucracy of Egypt took control over the environmental resources as well as the “biological lives” of the Egyptian peasants, leading to the loss of autonomy that the peasants enjoyed under Ottoman rule.

Ever since Mikhail published this work, environmental history has become a prominent trend in Ottoman history writing. Check this book out if you want to read a really good example of the genre.

If you’re interested to learn more about the Ottoman Empire, I’m currently developing a course that covers the Empire’s history from its early beginnings to the beginning of the 19th century. Check out the syllabus below.

Until next time!

Great list. I love Leslie Peirce’s book

Very good 👍👍